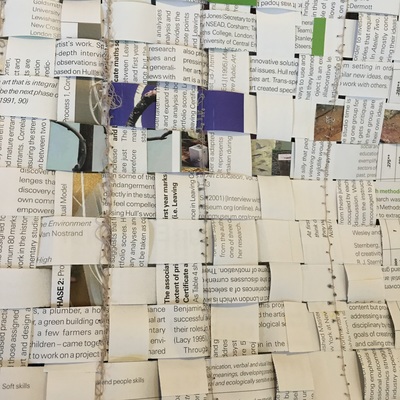

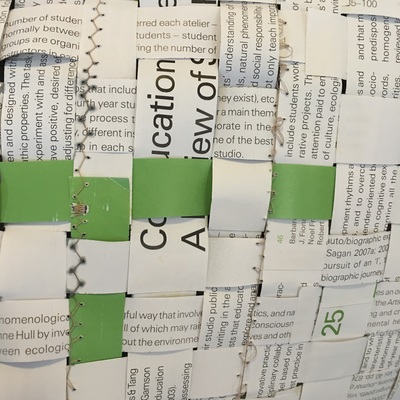

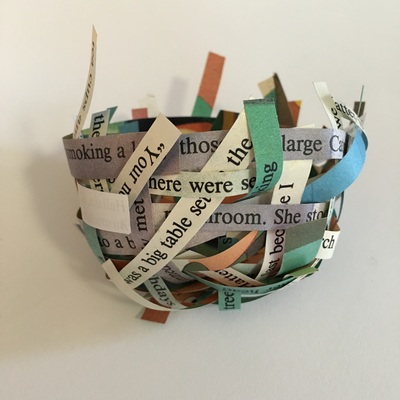

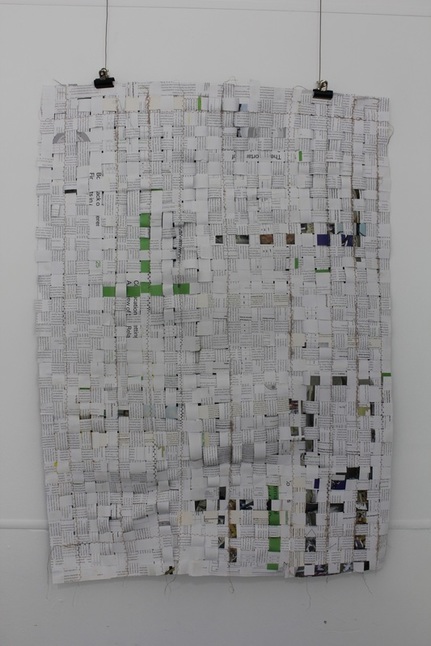

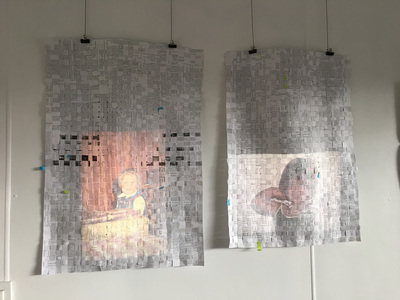

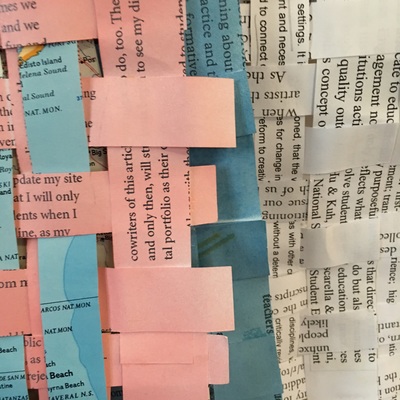

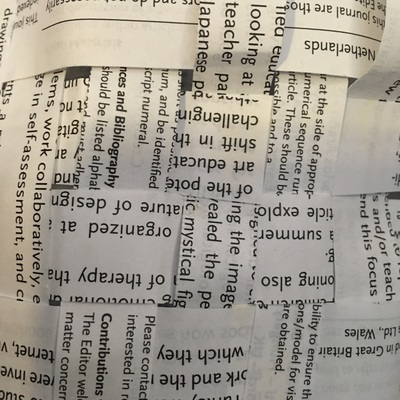

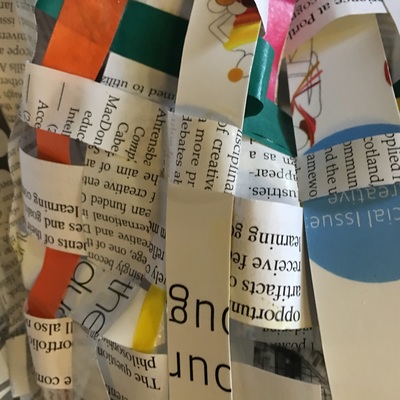

Cloud Collectors (trying to hold onto knowledge) Paper weaving (The International Journal of Education through Art) and maps, 2014-2016

Living Inquiry

“A/r/tography is a methodology of embodiment, of continuous engagement with the world, one that interrogates yet celebrates meaning” (Irwin & Springgay, 2008, p.xxix).

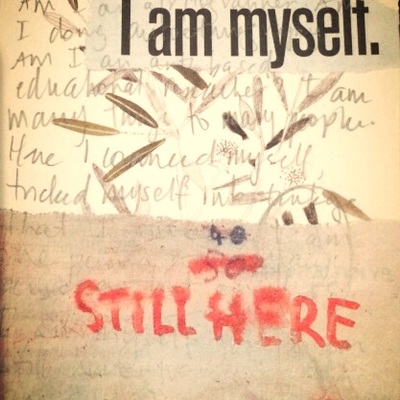

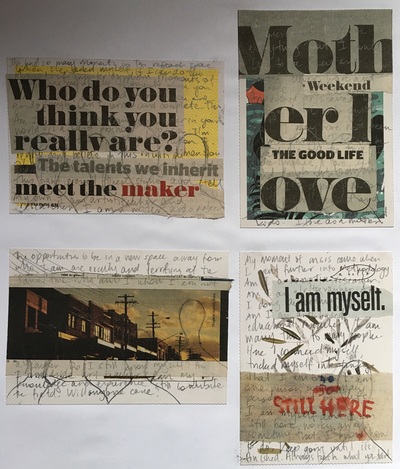

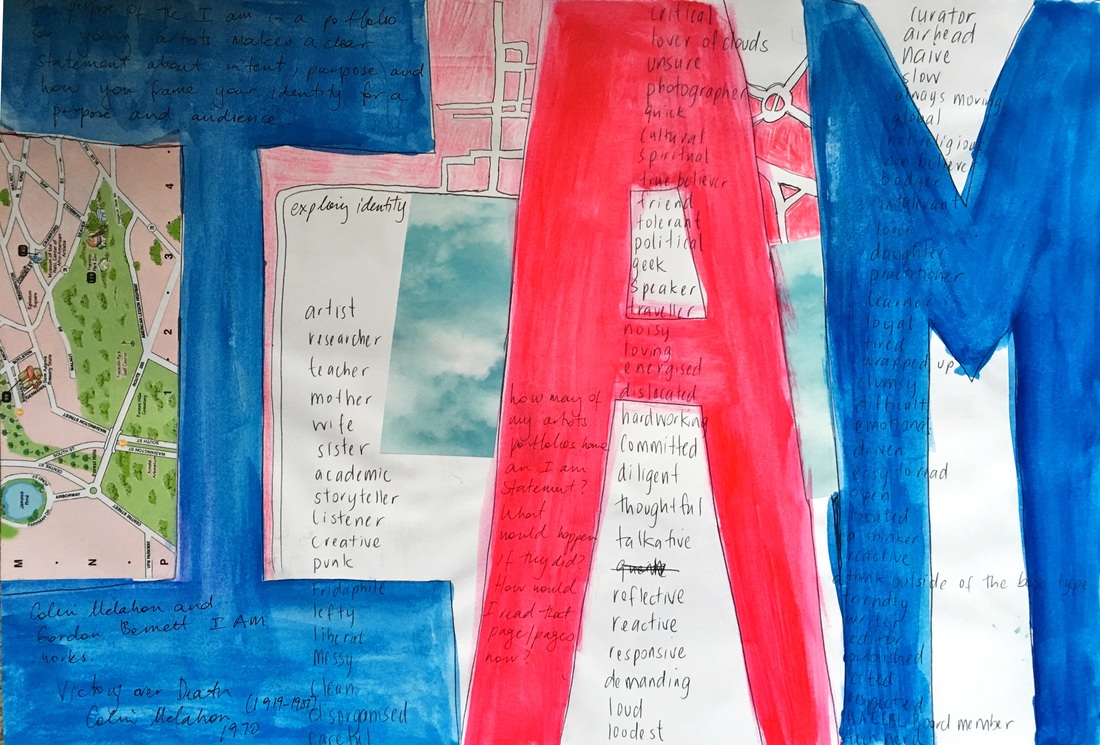

My identity as a/r/tographer has become more important, more integrative and more transformative through conversations, shared emails, phone calls and onsite video recordings living with the artist co-participant voices in this inquiry. They all continue to reverberate and resonate within my practice as a result of living with these art encounters, while developing and furthering my understanding and asking new questions of myself. I began to write this thesis deep within the living inquiry, often finding myself in a space of resistance as the ideas were in tension in wonderland. The artist co-participant voices needed to be woven amongst mine to demonstrate the rhizomatic, entangled and interconnected knowledge we have co-created, to re-create the conditions in which I have lived with their stories within mine. To create new openings for these ongoing internal conversations found gazing inwardly, I made art that allowed all of the voices in the inquiry to be made clearer. I cut, pasted, stitched and wove paper through different perspectives and points of view to re-position their thinking with mine and my field of inquiry then I began to curate this Portfolio.

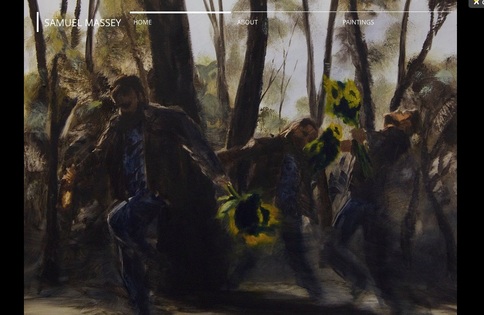

My living inquiry is curated here through the exhibition of selected stories, artworks, and ethnographic videos as digital objects in an art encounter. Curated as a living process and product of my praxis (Rolling, 2010) intertwined with my experiences, and embodied knowledge as a/r/tographer presented and opened in the digital to demonstrate the interwoven renderings of artful and lived inquiry in conversation with the shared stories. These shared stories with artist co-participants: Ahmad Sabra (Australia), Belinda Allen (Australia), Flavia Pedrosa Vasconcelos (Brazil), Glenn Smith (Australia), Laurie Gatlin (USA), Pam Frandina (USA), Pamela Griffith (Australia), Samuel Massey (Australia) and Zahrah Habibullah (Australia) are an important aspect of this study and my a/r/tographic philosophy. The recorded conversations are not interrogated or data drilled, rather curated as participatory artefacts that weave their way in and out of my thinking. As a result of meeting with each artist, reflection and now through our ongoing connections digitally, what has developed with each artist has become more important to my praxis as my living inquiry continues to unfold. Co-participation (Boylorn in Given, 2008) has allowed me as "the researcher to take on the role of student, allowing the research process to be a learning event” (p.599), archived and presented here.

My living inquiry is curated here through the exhibition of selected stories, artworks, and ethnographic videos as digital objects in an art encounter. Curated as a living process and product of my praxis (Rolling, 2010) intertwined with my experiences, and embodied knowledge as a/r/tographer presented and opened in the digital to demonstrate the interwoven renderings of artful and lived inquiry in conversation with the shared stories. These shared stories with artist co-participants: Ahmad Sabra (Australia), Belinda Allen (Australia), Flavia Pedrosa Vasconcelos (Brazil), Glenn Smith (Australia), Laurie Gatlin (USA), Pam Frandina (USA), Pamela Griffith (Australia), Samuel Massey (Australia) and Zahrah Habibullah (Australia) are an important aspect of this study and my a/r/tographic philosophy. The recorded conversations are not interrogated or data drilled, rather curated as participatory artefacts that weave their way in and out of my thinking. As a result of meeting with each artist, reflection and now through our ongoing connections digitally, what has developed with each artist has become more important to my praxis as my living inquiry continues to unfold. Co-participation (Boylorn in Given, 2008) has allowed me as "the researcher to take on the role of student, allowing the research process to be a learning event” (p.599), archived and presented here.

A digital portfolio site allows for the curation of the pages to have text, video and image to flow in and out of each other, here I could construct new dialogue in the curatorial imaginary to include the possibilities of participation in the digital (Runnel, Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt & Viires, 2013, p.9). As a result, I have rendered each chapter with a number of videos from each the artist co-participants throughout the text. To re-create the living here, I have curated the videos to speak and respond to me and to each other in conversation. To do so, I curated through an ongoing reflexive analysis and rhizomatic reflective process, where each video was reviewed, then cut and edited to be placed into the chapter text in response to my own provocation or vice-versa. Each of the artist’s 1 - 2hour long video discussions have been edited down to 2 - 5 minutes responses, edited as responses to my recursive, reflective responses.

The turn to the digital.

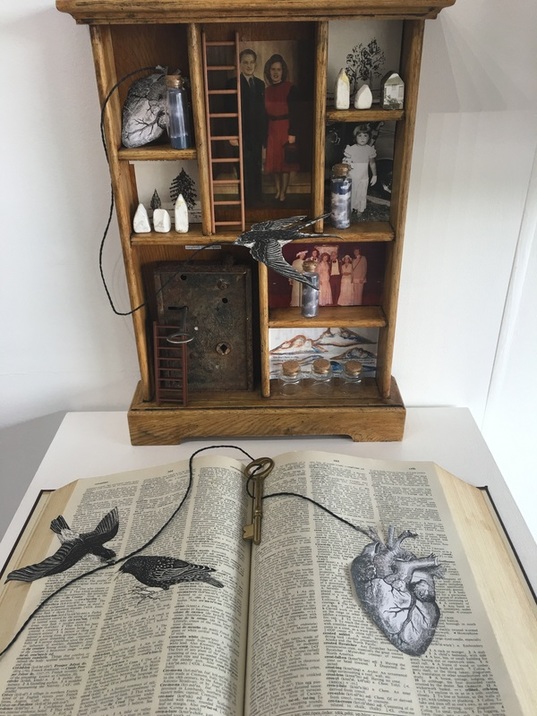

Belinda Allen

Belinda Allen

As an art teacher, my pedagogy is shaped by the curriculum and my a/r/tographical gaze. As an artist and curator my practice has a recurring theme of memory, layered and woven through form. From my graduating exhibition, an installation of ceramic vessels that were highly decorative and glazed only on the inside, to my latest series of paper works I can see the common thread throughout twenty plus years of practice - an embodied notion of hidden and disguised memory, story and self. Memories that are selected and chosen to be told, and retold as stories about the self. Having the ability to gaze back and forth throughout my practice is an important reflective skill and one that informs future work. This curated portfolio and living inquiry is a provocation to teach early career artists the skill of digital portfolio curation for critique as auto-ethnographer. As I have found through this process, a sustained digital portfolio collection and curation informs our aesthetic encounter ahead of time as artists. To support this pedagogical turn, this Portfolio is created and curated as a curriculum, designed and performed through an embodied scaffolding of my living learning and understanding of media and creative practice. I want to teach reflective practice through the gathering of our process and product of creative work, to create an opening to reflect on the artefacts developed through learning to learn as artist and art audience through the curation of personal artist collections.

“The curatorial begins when there is an appreciable surplus that calls for disruption. This does not mean that it begins when comfort is reached. This simply means that the curatorial begins as soon is the line is drawn, a fullness is recognised or a horizon of understanding is acknowledged” (Martinon, 2013, p.29). As a/r/tographers before me have indicated, the ruptures and interwoven voices and discourses often lie next to one another, but in tension. As with many border and neighbour disturbances, this tension brings difficulty to coherent and sustained writing for an a/r/tographer. Threads that seem common in the weave lead you to making, making often leads to further tensions and these interactions of discomfort continue.

Another epiphany.

Just as Martinon describes in The Curatorial, a/r/tographic praxis ‘begins when there is an appreciable surplus that calls for disruption’. Curating the self, as an a/r/tographer is an event, a becoming. In the way that Deleuze presents us with ‘becoming’. This event is rendered in the conceptual practices of the inquiry, creating a purposeful, tangled and untangled, imagined and reimagined curatorial. My artful inquiry led me to this understanding, not through the action of making, but in reflection on the event, in the curation of an a/r/tographic exhibition, when I curated an a/r/tographic site. In this Portfolio, I curate and piece together the a/r/tographic living inquiry. The curatorial imaginary is not only an action of presentation, of collection and curation, it is woven thoughts brought together out of the gaps, where the inbetween slashes between a/r/t provided a space for creativity to thrive. A/r/tography as a curatorial practice, “takes place on an indefinite, but finite horizon” (Martinon, 2013, p.29). “It is indefinite because like consciousness, it can never be fixed or limited: it always goes off, giving, disrupting, challenging preconceived orders, unsettling the firmly established” (Martinon, 2013, p.30).

Another epiphany.

Just as Martinon describes in The Curatorial, a/r/tographic praxis ‘begins when there is an appreciable surplus that calls for disruption’. Curating the self, as an a/r/tographer is an event, a becoming. In the way that Deleuze presents us with ‘becoming’. This event is rendered in the conceptual practices of the inquiry, creating a purposeful, tangled and untangled, imagined and reimagined curatorial. My artful inquiry led me to this understanding, not through the action of making, but in reflection on the event, in the curation of an a/r/tographic exhibition, when I curated an a/r/tographic site. In this Portfolio, I curate and piece together the a/r/tographic living inquiry. The curatorial imaginary is not only an action of presentation, of collection and curation, it is woven thoughts brought together out of the gaps, where the inbetween slashes between a/r/t provided a space for creativity to thrive. A/r/tography as a curatorial practice, “takes place on an indefinite, but finite horizon” (Martinon, 2013, p.29). “It is indefinite because like consciousness, it can never be fixed or limited: it always goes off, giving, disrupting, challenging preconceived orders, unsettling the firmly established” (Martinon, 2013, p.30).

The design of this Portfolio as site, is part of my living inquiry, a curated collection of digital images and digital text not published in a book, but here in an authentic digital portfolio installation as a pedagogical place, bound by poesis, praxis and theoria (Irwin & Springgay, 2008, p. xxiii). “Living inquiry is a life commitment to the arts and education through acts of inquiry. These acts are theoretical, practical and artful ways of creating meaning through recursive, reflective, responsive yet resistant forms of engagement” (Irwin & Springgay, 2008, p.xxix). As an art educator, curator and artist I have always been at that pivotal point of cultural change. I have to be. Art education and art encounters exist in a rhizomatic space, growing, changing, evolving. They are relational in the post-structural art world in which I live, work and theorise. “Art is this complex event that brings about the possibility of something new” (O’Sullivan, 2006, p.17).

“A/r/tography radically transforms the idea of theory as an abstract system distinct and separate from practice, towards an understanding of theory as a critical exchange that is reflective, responsive and relational” (Springgay, 2008, p. 160). This Portfolio is a site of a/r/tographic praxis, it is a space of process, a place of living rhizomatic inquiry curated as a relational space. Each of the thoughts, concepts, strategies and artefacts are curated in the story within the narrative of the rendered chapters. I draw here with conscious threads, that I have woven intentionally to develop the material connections between the a/r/tefacts. My knowledge, skills, experiences, education and creativity underpins this intent in curation. Looking through this lens of curation and digital storytelling in portfolios enables a shift in thinking for art educators to use our exhibition language of curation as well as storytelling that runs through our discourse as a device to construct new knowledge and creative practice through sustained and transformative reflection.

“A/r/tography radically transforms the idea of theory as an abstract system distinct and separate from practice, towards an understanding of theory as a critical exchange that is reflective, responsive and relational” (Springgay, 2008, p. 160). This Portfolio is a site of a/r/tographic praxis, it is a space of process, a place of living rhizomatic inquiry curated as a relational space. Each of the thoughts, concepts, strategies and artefacts are curated in the story within the narrative of the rendered chapters. I draw here with conscious threads, that I have woven intentionally to develop the material connections between the a/r/tefacts. My knowledge, skills, experiences, education and creativity underpins this intent in curation. Looking through this lens of curation and digital storytelling in portfolios enables a shift in thinking for art educators to use our exhibition language of curation as well as storytelling that runs through our discourse as a device to construct new knowledge and creative practice through sustained and transformative reflection.

|

Belinda Allen

Glenn Smith

|

As an a/r/tographer, my own art practice is woven as a narrative through the careful design and curation of my art, research and teaching in this Portfolio. It is curated here, woven with my practice and the co-participant voices in a space that offered me the creative possibilities of seamless display and a navigation that resembled a ‘traditional’ book for ease of use by participants and for assessment. This Portfolio site is skeuomorphic, the page morphs and moves with the screen size of the user, the page folds are neat, and I can easily embed video, text and images through placemaking. A skeuomorphic space resembles its living real world origin, in this instance a book as thesis.

Designed for the audience, this A/R/T Portfolio has a specific context and purpose for my communities of practice as a pedagogical site, an a/r/tographic installation of praxis as place, and the object of a digital dissertation as thesis. Just as physical “places are thought to similarly involve human intention and to be about things” (Andrews in Given, 2008, p.627) so to do digital portfolios as relational sites. Placemaking, space and site selection are important when choosing digital spaces as places for an audience. As a cartography and mapping of this living inquiry, this Portfolio's boundaries are determined by the artefacts and the audience initially, however, as a digital object and relational space it is theoretical, practical and participatory, just as Glenn refers to one of his sites and audience interactions. In contemporary qualitative research, place is thought of as a bounded phenomenon” (Andrews in Given, 2008, p.627). |

“Beginning as an action research approach, a/r/t-ography pursues ongoing engagements through living inquiry that is, continuously asking questions, enacting interventions, revising questions, and analyzing collected data, in repeated cycles. While practicing their art forms and their pedagogy, a/r/tographers are committed to knowledge creation that is rhizomatic in nature, complex in its entirety, and enhanced with aesthetic understandings (Irwin, 2010, p.1).

The design of this Portfolio as site, is as a sustainable living inquiry beyond the life of the PhD boundaries, through the mapping of the journeys in an authentic digital portfolio installation as a pedagogical place. The curation of this site has been designed to provide an insider perspective on embodied and performed praxis, as “reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it” (Freire, 2000, p. 51) and digital portfolio creative design and development. “The act of reflection through portfolios not only allows students to review their current progress and evaluate their own skill acquisition, but also can facilitate the active process of retrieving knowledge in order to apply it to a novel situation and increase students’ ability to reach higher order thinking skills, such as comparing, analyzing, and drawing conclusions on the material in which they are focusing” (Bowman, et al., 2016, p.2).

A/R/T

“The forms that [the artist] presents to the public [does] not constitute an artwork until they are actually used and occupied by people” (Bourriaud, 2004, p.46).

Positioning digital portfolios in art education

I know that digital portfolios are pedagogically important collections of self directed and curated learning. I have worked in them and with them in educational research and practice for a long time (Yang, Coleman, Das & Hawkins, 2014; Coleman & Rourke, 2010; Rourke & Coleman, 2009; Rourke, Mendelssohn & Coleman, 2008). What I sought to prove if you will in this living inquiry, is how important they are to visual art education and creativity in art classrooms as relational spaces that invite participation by an art audience as we create new openings in the rhizomatic digital world.

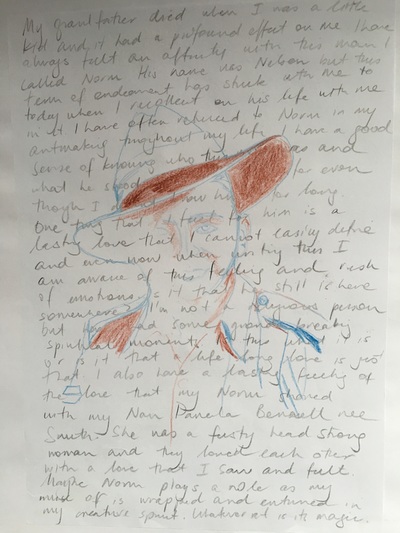

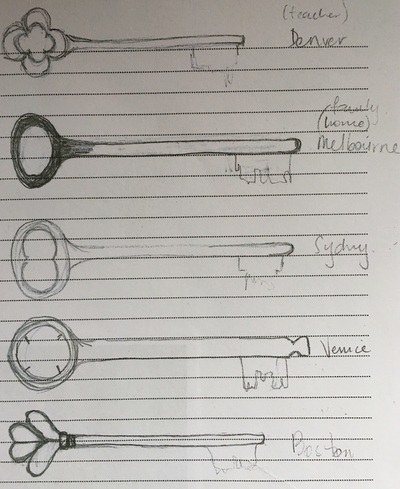

I went back to the literature, to locate and cluster my seminal thinkers and synthesise their research through the use of visual metaphor for sense-making. This layered rhizomatic discourse analysis (Honan & Sellers, 2011), is invisible learning as you read this Portfolio, however it holds this collection of artefacts together in wonderland. Making visible the connections through art and writing are important for a/r/tographers and this rendering allows for meaning making. “To be engaged in a/r/tography means to inquire in the world through both processes, noting they are not separate or illustrative processes but interconnected processes” (Irwin & Springgay, 2008, p.xxviii). I would make art, write my field notes in endless notebooks and sketch books, drawing and writing in the margins of the seminal texts creating marginalia and then continue, stopping to turn as the reflection lead or turned. I began in the growing literature of portfolios for reflection (Buyarski & Landis, 2014; Hassan, 2011; Parkes, Dredger & Hicks, 2013; Wong & Trollope-Kumar, 2014; Yueh, 2013) and portfolios for learning (Allen & Coleman, 2011; Klenowski, Askew & Carnell, 2007; Penny Light, Chen & Ittelson, 2012; Yancey, 1992; 2004; 2009), a space I inhabit as a researcher outside of this study. I started here because I needed to gaze, to wonder and to see, to notice through a different lens, that of a/r/t. I began by drawing and creating visual metaphors of the research artefacts I was re-searching. I created visual categories of metaphoric collections, a digital backpack for roaming and wandering.

I went back to the literature, to locate and cluster my seminal thinkers and synthesise their research through the use of visual metaphor for sense-making. This layered rhizomatic discourse analysis (Honan & Sellers, 2011), is invisible learning as you read this Portfolio, however it holds this collection of artefacts together in wonderland. Making visible the connections through art and writing are important for a/r/tographers and this rendering allows for meaning making. “To be engaged in a/r/tography means to inquire in the world through both processes, noting they are not separate or illustrative processes but interconnected processes” (Irwin & Springgay, 2008, p.xxviii). I would make art, write my field notes in endless notebooks and sketch books, drawing and writing in the margins of the seminal texts creating marginalia and then continue, stopping to turn as the reflection lead or turned. I began in the growing literature of portfolios for reflection (Buyarski & Landis, 2014; Hassan, 2011; Parkes, Dredger & Hicks, 2013; Wong & Trollope-Kumar, 2014; Yueh, 2013) and portfolios for learning (Allen & Coleman, 2011; Klenowski, Askew & Carnell, 2007; Penny Light, Chen & Ittelson, 2012; Yancey, 1992; 2004; 2009), a space I inhabit as a researcher outside of this study. I started here because I needed to gaze, to wonder and to see, to notice through a different lens, that of a/r/t. I began by drawing and creating visual metaphors of the research artefacts I was re-searching. I created visual categories of metaphoric collections, a digital backpack for roaming and wandering.

|

I further discuss the importance of metaphors in a/r/tography, for a/r/tography and portfolio curation in the next rendered chapter, however, this connectedness is important in my discussion here on rhizomes and portfolios in the living inquiry and the inherent aspects of a/r/tographic pedagogy through the lens of art. Within the literature of portfolios for reflection and learning, my mapping of the metaphors along the journey found ‘making learning visible’ (Johnsen, 2012); learning and ‘designing’ (Gunn & Peddie, 2008; Hicks, Russo, Autrey, Gardner, Kabodian & Edington, 2007; Zhang, Olfman & Ractham, 2007); ‘digital stories’ (Barrett, 2014; Coleman, 2014); portfolios as ‘living documents’ (Oliver & Whelan, 2011; Woodley & Sims, 2011; Cambridge, 2008); ‘eportfolios for identity’ (Coleman, 2014; Fenton, 2011; Cambridge, 2010) and, ‘eportfolios for engagement’ (Housego & Parker, 2009; Oliver, Nikoletatos, von Konsky, Wilkinson, Ng, Crowley, Moore, & Townsend, 2009; Raiker, 2009; Hallam, Harper, McCowan, Hauville, McAllister, & Creagh, 2008; Tosh, Penny Light, Fleming & Haywood, 2005). So many visual metaphoric openings that allowed me to reflect on reflections on reflections as they reverberated and reflected new images back at me.

|

This clustering of the literature visually and metaphorically made clear the use of layered and meaning laden language by the authors to show how portfolios are deep, reflective collections that support transformative and integrative experiences for students. It allowed me as an insider in that research world to find a path into art education through my creative practice along a branch of the rhizome root. This experience is important for it underpins this A/R/T Portfolio as a mapped space for rhizomatic, relational renderings, that occur through ongoing reflection in and of portfolios as threshold and transformative (Perkins, 1999) practices. Practicing the methodology in the inbetween, liminal spaces, shifted my “perspective...lead[ing] to a transformation of personal identity, a reconstruction of subjectivity” (Meyer & Land, 2003, p.4) and becoming. From metaphor and visual image of researcher I shifted my focus to making art as research, not only writing and reading as researcher.

To work within the metaphor more physically, I have been working in paper narratives as an a/r/tist through the collection of paper artefacts such as maps and torn, folded and cut up research papers as part of my 'written' research that I then weave, fold and generate new dialogue with as an artist throughout this study. My artmaking is a sense making process that sits alongside my writing, rhizomatic writing that is reflexive, reflective and autoethnographic. These embodied and performed responses are critical analysis and create the conditions for this living inquiry to take the narrative and creative turn it has. This rhizomatic journey offers new opportunities at each growth point for a/r/tographers in the living art research landscape. On this journey, I have activated site by asking questions of the space and following the rhizome as it leads me as an artist, researcher, teacher always influenced by a process of critical dialogue through exhibition in the physical and virtual. This criticality, is an unfolding process of relational and rhizomatic work that has created a new conceptual art practice. Woven, intertwined and encountered. It runs through and over a/r/tographical renderings (Irwin and Springgay, 2008. p. xxvii) through my contiguous selves.

To work within the metaphor more physically, I have been working in paper narratives as an a/r/tist through the collection of paper artefacts such as maps and torn, folded and cut up research papers as part of my 'written' research that I then weave, fold and generate new dialogue with as an artist throughout this study. My artmaking is a sense making process that sits alongside my writing, rhizomatic writing that is reflexive, reflective and autoethnographic. These embodied and performed responses are critical analysis and create the conditions for this living inquiry to take the narrative and creative turn it has. This rhizomatic journey offers new opportunities at each growth point for a/r/tographers in the living art research landscape. On this journey, I have activated site by asking questions of the space and following the rhizome as it leads me as an artist, researcher, teacher always influenced by a process of critical dialogue through exhibition in the physical and virtual. This criticality, is an unfolding process of relational and rhizomatic work that has created a new conceptual art practice. Woven, intertwined and encountered. It runs through and over a/r/tographical renderings (Irwin and Springgay, 2008. p. xxvii) through my contiguous selves.

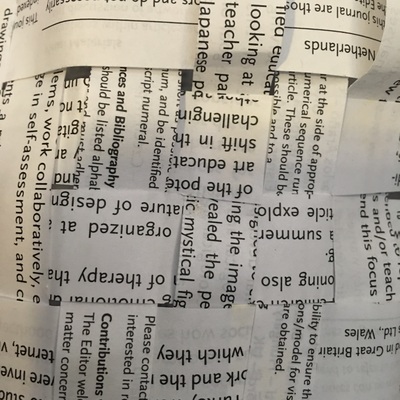

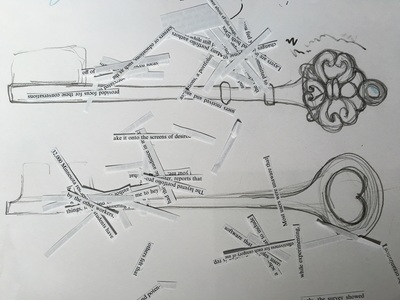

For years my house has been scattered with cut up academic papers. I began to work in paper to better understand contiguity. To consider the folds, the connection and the borders of a/r/tography to work in the conceptual practices. I started metaphorically. What occurred as I continued to work as with all sustained creative practice, is that the gaps created new widened spaces, the experience of being in wonderland led to new paths of discourse in paper art and site specific installations. New possibilities, new forms, new ways of working through curating, pasting, drawing, weaving. I went and studied weaving with a leader in the Australian art community. I studied origami and the art of paper folding. I continued to work in paper, exploring its potential as an art medium. This is a digital thesis, so working in paper I felt was a necessary contiguity between the situated and the digital spaces. What place would my thesis hold in the physical world that universities still hold so dear if there was no paper artefact? These artworks and the exhibition at Virgin Walls were my paper submission, discursive, deliberate and disruptive as a digital pedagogue. The process of cutting became habitual. After reading the article, book, paper, I would draw, reflect, read again, make notes in my note book soaking up the content and acquiring as much as I could take in. Then cut it up. Each line. Line by line I would cut the thoughts, ideas and thinking, dismantling the constructed theories and research artefact. People offered me assistance, shredders. However, this process was a catharsis, it was personal. I was constructing new ideas. The paper had become a part of my thinking and no longer needed to exist in its physical form, as academic discourse, it was now a thread in my dialogue, physically woven and threaded, pasted and stitched with other fields of study to create new discourse for my art education community. Papers, articles and journals that are to be found here digitally, connected and referenced in my thinking are all bound together, transformed into woven, folded and layered objects and artworks.

The cut up process included cutting an article or page up every 2-3 lines, then laying out the strips horizontally on the ground in my studio like venetian blinds, in parallel to each other. Then I would wait until another paper was read, folded into my thinking and then I cut it up, placing its lines in the gaps. Once I had the size of work I was after I would start with the vertical lines running the other way. Following the lines in the cut ups, I would ensure that another discourse, another field would join the end, creating new dialogue, opening opportunities for the overlap of my fields of inquiry in creativity, art education, portfolios, digital pedagogies and a/r/tography to join together and work as one.

The cut up process included cutting an article or page up every 2-3 lines, then laying out the strips horizontally on the ground in my studio like venetian blinds, in parallel to each other. Then I would wait until another paper was read, folded into my thinking and then I cut it up, placing its lines in the gaps. Once I had the size of work I was after I would start with the vertical lines running the other way. Following the lines in the cut ups, I would ensure that another discourse, another field would join the end, creating new dialogue, opening opportunities for the overlap of my fields of inquiry in creativity, art education, portfolios, digital pedagogies and a/r/tography to join together and work as one.

|

The Dada artists were interested in the spaces, the gaps, the cutouts. ‘Cut up’ works of this time reflect the contiguity of a/r/tography, where relationships, identities and spaces fold, weave and grow as a rhizomatic ginger plant. “In late 1920, the Dadaist writer Tristan Tzara wrote “dada manifesto on feeble love and bitter love,” which included a section called “To Make a Dadaist Poem,” and it gave these instructions: Take a newspaper. Take some scissors. Choose from this paper an article of the length you want to make your poem. Cut out the article. Next carefully cut out each of the words that makes up this article and put them all in a bag. Shake gently. Next take out each cutting one after the other. Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag. The poem will resemble you. And there you are – an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd” (Tristan Tzara, “To Make a Dadaist Poem” in Colman, 2011, NPN). |

The more that I cut up, wove, and folded art works, the closer I was to understanding and creating new thinking for art. Sustained practice and deep learning and practice in any field is hard work, it takes diligence and commitment. I worked harder, longer and produced more work that I was happy with the longer I worked to resolve and reflect in action.

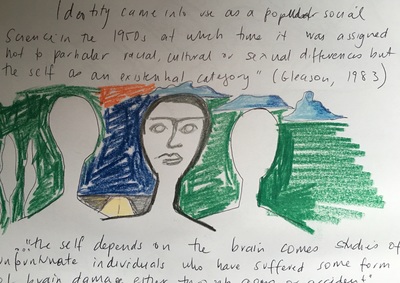

Being with creativity through sustained practice presented an embodied knowing, and opened the opportunities for deep learning through portfolio development in art for students. “Practice develops the ability to use materials and techniques intelligently, imaginatively, sensuously and experimentally in order to respond to objects and ideas creatively through personally meaningful, communicable artefacts in school, later life or professionally” (Swift & Steers, 2006, p.18). This kind of sustained engagement is critical, reflective and transformative for artists as we develop our practice and sense of self as artist. A/r/tographer Suominen Guyas (2008) proposes, “it is my goal to guide my students toward critical awareness of identity construction that is not limited to given and pre-accepted categories and classifications” (p.25). Deep Practice or deeper learning competencies as it's called in schools (William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, 2013) is a framework of competencies for problem based, experiential and critical thinking tasks that are developed over time, designed and ideated following a design thinking model and involve ongoing feedback cycles. This kind of curriculum design requires built in opportunities for sustained and deep learning. In art these openings can allow for the development of identity as artist, not through learning about others as Artists, but through learning about the self through artful inquiry over time. Sustained practice and deep learning is focused creative practice that grows, builds and develops through ongoing skill and technical engagement.

Being with creativity through sustained practice presented an embodied knowing, and opened the opportunities for deep learning through portfolio development in art for students. “Practice develops the ability to use materials and techniques intelligently, imaginatively, sensuously and experimentally in order to respond to objects and ideas creatively through personally meaningful, communicable artefacts in school, later life or professionally” (Swift & Steers, 2006, p.18). This kind of sustained engagement is critical, reflective and transformative for artists as we develop our practice and sense of self as artist. A/r/tographer Suominen Guyas (2008) proposes, “it is my goal to guide my students toward critical awareness of identity construction that is not limited to given and pre-accepted categories and classifications” (p.25). Deep Practice or deeper learning competencies as it's called in schools (William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, 2013) is a framework of competencies for problem based, experiential and critical thinking tasks that are developed over time, designed and ideated following a design thinking model and involve ongoing feedback cycles. This kind of curriculum design requires built in opportunities for sustained and deep learning. In art these openings can allow for the development of identity as artist, not through learning about others as Artists, but through learning about the self through artful inquiry over time. Sustained practice and deep learning is focused creative practice that grows, builds and develops through ongoing skill and technical engagement.

|

Many questions continue to arise throughout the curation of this living inquiry: "Do the arts inform the inquiries we conduct? Do our inquiries inform the arts/the way we do our art making? Do we need both (ie., research) and arts to form and inform one and the other in our understandings of teaching and learning others and ourselves?" (Gouzouasis, 2008, p.228) |

Belinda Allen

|

Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990) flow is critical for practice that is sustained in deep learning for creativity. We are often so focused on driving our students through experiences and skills, having opportunities to experience media and materials and having products as a result of artmaking that we rarely create the space for our students to create and learn in a state of flow through sustained deep learning. Csikszentmihalyi (1990, p.4) states that optimal flow requires a number of conditions, three ring true for me as artist-teacher:

1. clarity of both long-term and moment-to-moment goals,

2. an immediate feedback loop that gives information about the individual’s progress toward achieving those goals, and

3. a balance between the challenges presented and the skills the person possesses.

To further this sustained practice or deep learning in our studio classrooms for creativity, assessment for learning that is authentic for artists is an important aspect of the portfolio learning design. “Assessment should be authentic, i.e., reject testing in favour of procedures which require students to engage in long-term, complex, and challenging projects reflecting real-life situations. Data collected for analysis include portfolio evidence of developmental work, written or recorded (student reflections), and teacher-student dialogue (Swift & Steers, 2006, p.23).

1. clarity of both long-term and moment-to-moment goals,

2. an immediate feedback loop that gives information about the individual’s progress toward achieving those goals, and

3. a balance between the challenges presented and the skills the person possesses.

To further this sustained practice or deep learning in our studio classrooms for creativity, assessment for learning that is authentic for artists is an important aspect of the portfolio learning design. “Assessment should be authentic, i.e., reject testing in favour of procedures which require students to engage in long-term, complex, and challenging projects reflecting real-life situations. Data collected for analysis include portfolio evidence of developmental work, written or recorded (student reflections), and teacher-student dialogue (Swift & Steers, 2006, p.23).

|

Pink cloud hovers, eerily suspended over mountain top. Iridescent in moonshine, it capers around a stand of stately, somber cedars and cavorts with long-stemmed winter grasses like some winsome spirit in a medieval cloak. Vanishing mysteriously, it leaves no trace of origin. A gift of sky. Night Vision, Virginia Gow, Blackheath, NSW |

In Blackheath at the gallery, I met Australian artist and poet Virginia Gow. Virginia visited the gallery most days to talk about art and discuss my cut up and folded works, cloud metaphors and digital art education pedagogy. We talked about words, art and practice developed overtime. She shared her work with me and said I could cut them up. She would love me too.

I read many of her Fibonacci poems in Blackheath during the week and found our common threads, in our love of the Mountains, in artistry and artful inquiry as artist researchers.

In her book, Escarpment - Fibonacci poetry (2013), Virginia uses the Fibonacci sequence of numbers in her construction of words and artful ideas by counting the syllables in the words to determine the length of the line that she writes. My favourite from my week of reading and writing, is this poem called Night Vision.

I read many of her Fibonacci poems in Blackheath during the week and found our common threads, in our love of the Mountains, in artistry and artful inquiry as artist researchers.

In her book, Escarpment - Fibonacci poetry (2013), Virginia uses the Fibonacci sequence of numbers in her construction of words and artful ideas by counting the syllables in the words to determine the length of the line that she writes. My favourite from my week of reading and writing, is this poem called Night Vision.

(Re)search

“ePortfolios present work in a structured fashion and the viewing of the portfolio has a temporal unfolding that can be understood as a performance. The way the ePortfolio is structured and the types of interactions with it that are allowable, frame the presentational opportunities and thus the performativity of the ePortfolio” (Dillon & Brown, 2006, p.5). Much of the published research on portfolios predominantly uses the ‘e’ in front of portfolio. I have chosen not to do this and to use digital portfolio because this study is not about technology or platform specific uses of portfolios for institutions, a great amount of evidenced based research has already been captured. I am choosing to re-search and shift my language toward digital portfolios to re-position the portfolio politically in art education and with that, more in the realm of the rhizomatic inter-web, in the digital wonderland for creativity. Digital portfolios are curated spaces that allow for presenting, designing and curating online views of web ready pages in open source portfolio spaces such as websites, blogs, microblogs etc. This is an important point of difference because it provides autonomy to the curator to select a tool and space that offers them the creative freedom to present who they are, and the creativity to present and compose the pages and presentation the way that they want it to be read by an audience. We do know that “ePortfolios have the potential and the capacity to awaken the silenced voice, embodied knowledge and to get closer to representing the presence of artistic practice for reflection, analysis or assessment” (Dillon & Brown, 2006, p.2), here, now in the digital, a decade after this paper was published we have new openings.

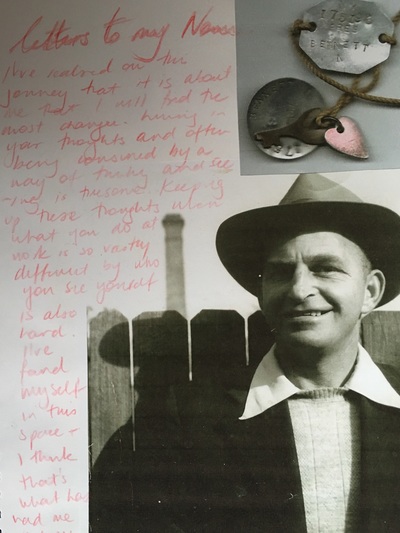

Zahrah Habibullah

Of the many epiphanies in this study, one shining moment as a/r/tographer is the ability to see through different eyes, that of curator. Curator of content, context, community and cite as artist, researcher and teacher. Contiguity brings with it new lenses in a living inquiry, where the study is embodied through continuous engagement. This seeing happened through noticing the curation of storied collections here in site. Sameshina (2008) calls this AutoethnoGRAPHIC Relationality. “AutoethnoGRAPHIC Relationality is thus writing and rendering autobiography and ethnography in vivid detail braiding all aspects of living, learning, researching, and teaching in context” (Sameshina, 2008, p. 50). Working with portfolios, I have the opportunity to see and read many stories of learners and learning, seeing the world as an “accidental ethnographer” (Poulos, 2014, p.9) and bring this to art education.

Writing auto-ethnography is personal, performative, reflective and embodied. Working as a/r/tographer is where the layering begins and the selves intertwine. I live with my stories, they are my experiences, always tangled in the histories of others, but mine to recollect and choose to share. With these stories I create new dialogue and discourse with each new book, artwork, paper or lead. These turns are performed, they shift sight and open site for new opportunities. Doing ethnography is something quite different, holding another’s living inquiry that you opened the lid on, is eventful. I have each of the artist's hearts, minds and souls in my head and heart, and recorded on my computer. They have given me their stories, allowed me to record our conversations as digital artefacts and allow me to weave throughout my own. Each of them have entrusted me with their words, their ideas, their voice and their lives, their practice. They are not data; they are co-participants in my community of practice. I came to the realisation that this ‘doing of ethnography’, is part of my becoming and being as a/r/tographer. As Poulos, states more perfectly that I could, “I did not seek it out. I stumbled upon it” (Poulos, 2014). “Negotiating personal engagement within a community of belonging is part of the rhizomatic relationality of inquirers working together. A/r/tographers are continuously negotiating and renegotiating their foci as the community’s research and inquiry evolves and shifts over time” (Irwin, 2008, p. 77). This is the heart of digital portfolios in art education, they are personalised story collection sites.

Writing auto-ethnography is personal, performative, reflective and embodied. Working as a/r/tographer is where the layering begins and the selves intertwine. I live with my stories, they are my experiences, always tangled in the histories of others, but mine to recollect and choose to share. With these stories I create new dialogue and discourse with each new book, artwork, paper or lead. These turns are performed, they shift sight and open site for new opportunities. Doing ethnography is something quite different, holding another’s living inquiry that you opened the lid on, is eventful. I have each of the artist's hearts, minds and souls in my head and heart, and recorded on my computer. They have given me their stories, allowed me to record our conversations as digital artefacts and allow me to weave throughout my own. Each of them have entrusted me with their words, their ideas, their voice and their lives, their practice. They are not data; they are co-participants in my community of practice. I came to the realisation that this ‘doing of ethnography’, is part of my becoming and being as a/r/tographer. As Poulos, states more perfectly that I could, “I did not seek it out. I stumbled upon it” (Poulos, 2014). “Negotiating personal engagement within a community of belonging is part of the rhizomatic relationality of inquirers working together. A/r/tographers are continuously negotiating and renegotiating their foci as the community’s research and inquiry evolves and shifts over time” (Irwin, 2008, p. 77). This is the heart of digital portfolios in art education, they are personalised story collection sites.

As an active researcher in my communities of practice, I am privileged to have the opportunity to speak and ask questions of the leaders, innovators, and disruptors in education in person or through social media. I live in a number of professional learning communities as a researcher and practitioner, in the digital educational technology space, in the art space and as an educationalist. I love this global learning community of practice that allows me to live between, in the spaces between art, research and education, “locating researcher in a contiguous dynamic of collaborative practice” (Fendler, 2013, p.789). I feel very honoured that these seminal thinkers share so much with me. This ongoing discourse with change makers and innovative educationalists is a powerful part of who I am and how I approach research. One defining aha! moment that sets the scene for the chapters that follow came in an ePortfolio research meeting in America in 2013. We were discussing reflective practice and the role of metacognition in portfolio practice for higher education learners. I used the term curation to describe what it is that we as artists do when we reflect on a selection of artefacts and then design, compose, lead, narrate and create a web page or digital space as a portfolio. These portfolios for artists have a range of purposes, from sites to sell work, to digital monographs. I refer to them all as portfolios because they are purposeful, curated, relational spaces that when composed create a place for an audience to view, interpret, participate, critique and understand. My understanding of the term and practice of curation was different from my colleagues at this meeting. They thought that I used it in a particular way that was metaphoric, my AHA! moment was having to define and redefine it, ending with I don’t think you understand what I’m describing this praxis to be. I saw in plain site how misconstrued educational language, well all language is when used out of context. My understanding was laden in cultural and disciplinary layers, not the way that it is used to define digital curation or what I call thematic digital collections and this paved the way for future making, doing, and writing about portfolios.

For research, curating the artefacts of this evolving study has been an integral aspect of the ‘autoethnoGRAPHIC’. Video ethnography (Harris, 2016) has opened the door to a research method that I had included in my researcher toolkit as a/r/tographer without considering its role in the living inquiry. I took for granted that I was working in digital forms, that I could film, edit and make videos as a Film and Media teacher. I hadn’t considered the impact of gazing back over recorded footage and re-examining my co-participants in context as researcher when I cut, digitally embodying the cut up I had worked on in my paper works. I was artist-teacher upon reflection of the initial recorded discussions. Each conversation, brought with it further familiarity, it was like I knew these artists, like old friends. Belinda, Glenn and Zahrah I knew from my life as artist and art teacher in Sydney, they had answered my social call out and volunteered their stories. The others I had never met before, we had people we knew in common obviously because we’re somehow connected online through twitter or Facebook, but our experiences and sense of self is interestingly similar in other ways.

The common threads of the artists in this inquiry weave this Portfolio.

The common threads of the artists in this inquiry weave this Portfolio.

|

Reflection on praxis is profound and (re)collection alters your point of view. The weaving of practice with theory has been an evolving and iterative process to becoming. This living inquiry has altered my way of knowing, doing and relating to a/r/t. I loved talking with my co-participants during the collection of stories. The realisations, the common threads, the new insights that they opened for me were exciting and have never left my thinking on the role that portfolios need to play in younger artist lives as a result of their reflections, sustained practice and experience of being, artist. As ethnographer, I have now shifted sight to review and then curate these stories here among my stories of a/r/t. Within praxis, I embody a knowing of self. I am now always looking for something, not merely listening and discussing, I am noticing. A shift and turn to praxis that took me from researcher to teacher, back to artist and now to a/r/tographer as I have curated all of the cut-up voices here together Working back as editor and researcher in these videos, rather than as collector has allowed me to further synthesize their stories, and consider how to apply and curate them in this Portfolio throughout my story for the audience as re-searcher.

|

Down, down, down. Would the fall never come to an end? “I wonder how many miles I’ve fallen by this time? She said aloud. “I must be getting somewhere near the centre of the earth”. (a/r/tographical Renderings, After the Cloud Atlas)

Digital Image, 2015 |

Helen Chen from Stanford University is one of the go to people of the ePortfolio community. She is the caterpillar in Wonderland, a clever, curious and creative research scientist. She has written or co-written many seminal texts in the field, and she is also a lovely friend and mentor. In 2015, Helen invited me to join her in a keynote for the ePortfolio community at the Association of Authentic, Experiential and Evidence-Based Learning Annual Conference. I would be joining Dr Gary Brown, Senior Fellow with the Association of American Colleges and Universities and, Ashley Kehoe, Experiential Learning director from Dartmouth College - and Me, from Melbourne. An explorer and searcher, still looking, still gazing, would be joining them. We collaborated on our approach, and commitment to inviting the audience into our differing views and lenses on learning, portfolios and assessment for learning. Each us were to bring something new, something different to the conversation as a Day 2 Keynote and extend thinking on where we have been, and where we are now in ePortfolios. We settled on the working theme of Back to the Future. We were presenting in Boston in 2015, in the same city and year that Marty McFly rides on his hover board in the future. Our resolve was to explore our different perspectives through a conversational style keynote called Back to the Future: ePortfolio Pedagogy Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. I was to be the last of four speakers and provide some predictions about the future of ePortfolios and the growing practice of Open digital badges for verifying portfolio evidence (Gibson & Coleman, 2016). I told a story. My story of portfolios, with pictures from my first curated scrapbooks that my mum made, through to my latest verified and endorsed collection site in LinkedIn. I talked through yesterday, today and tomorrow as an artist, researcher and teacher presenting the artfulness of Portfolios in the past and creativity of Portfolios for the future. I concluded that the future of portfolios in education would be about the following themes, issues and topics: granularity, personalised learning, integrative learning, trans-disciplinary learning, employability, prior learning, learning ecosystems, assessment for learning, evidence of and for learning, audiences of and for learning, learning experiences, transformative learning, adaptive learning, credentials of/for/as learning, and, competency based learning. The last line on my final slide read: ‘We hold many of the answers today because we understand evidence, audience and context’. This was directed to the whole ePortfolio community, more interestingly, this is where our differences lie as I practice as a/r/tographer, performed on a slant (Beard, 2016).

Teach-ing

In the digital space, an artist portfolio is another world for the artist to inhabit. A site for exploration of self as artist, where there are new possibilities, new opportunities for new audiences and new connections to make through reflection on practice and presentation of works alongside each other. This reflection on reflection, on reflection as metacognitive activity opens the door through “thought or reflection. ...[and] is the discernment of the relation between what we try to do and what happens in consequence. No experience having a meaning is possible without some element of thought” (Dewey, 1916, p. 169). In a digital portfolio, this thought process allows an artist to self curate new exhibitions of work, develop new narratives about their practice and invite new conversations and dialogue between works and audience. A portfolio or digital web site, is an exploratory world where the artist is researcher, designer, curator, and teacher in contiguity.

|

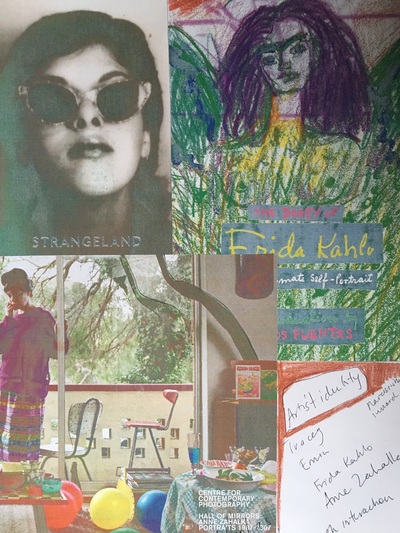

The invisible learning mentioned here is typical of the reflective practice cycle of portfolio pedagogy as well as much of digital learning that happens in the root structure of the rhizomatics of the web. The next step of portfolio creation is relational, through the defining of systems for the audience through self reflection, gazing inwards to capture collections in themes. My art making explored this concept of systems design through listmaking, compartmentalising ideas into categories and the creation of a memory wunderkammer.

|

Just as we move through the levels of complexity for sustained deeper learning, portfolio artefact synthesis through design thinking, is as Biggs (1995) designed in his Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome (Solo) Taxonomy, defined as a developing and deepening of understanding. This is achieved in the space of the portfolio, where by the curator begins to refine and catalogue artefacts collected that sit most neatly at the centre of the inquiry – the purpose of the portfolio. Just as a designer, who works toward a design brief, a portfolio is designed for specific purposes and in contexts where deep and transformative learning are important to the self efficacy of the learner. “When [e]Portfolios are focused on process rather than product alone (i.e., how students have made sense of ideas over time), they can become a tool for identifying and supporting metacognition, allowing students to look into their prior, current, and post-educational experiences and “to talk across them, to connect them, to trace the contradictions among them, and to create a contingent sense of them” (Yancey, 2009, p. 16)” (Bosker et al, 2016, p. 33). This self organisation of content is both a digital literacy, visuacy skill and communication set of competencies for learners to develop throughout their art education. “Knowledge is relational, dependent on contexts and philosophy, and can not be separated from an understanding of the self and its multiple embedded identities” (Suominen Guyas, 2008, p.25). Similarly, to Dillon and Brown (2006), I design portfolio learning opportunities as living inquiries, or “as a performance” (p.418) for creative becoming.

This becoming as artist and artist-student as learner is one of the provocations of this a/r/tographical study: What can we learn from artist portfolios to inform art education?

This becoming as artist and artist-student as learner is one of the provocations of this a/r/tographical study: What can we learn from artist portfolios to inform art education?

|

Making decisions, planning, reflecting and organising practice for an audience beyond the physical site of the studio or gallery is required for the curation of artist identity artefacts in portfolios. The curated portfolio is a space where both process and product interplay, where the physical and digital intertwine, where art and research speak with the past and the present and create new dialogue across a body of work, thematically, chronologically or genre based. It is not often that an artist sees their work all displayed in one space, in one room, in sight, on site. Here in Sam Massey’s digital portfolio or artist web site, he has opened the possibilities for seeing the common threads and woven stories through his works that have not had the opportunity to be seen together across years, genres, themes and media. This was done for his audience, most notably, it connected with him.

|

A commitment to relational and rhizomatic a/r/t praxis

Discovering and researching within my collections of artefacts to find what is that I know about art education, creativity and portfolios has been as much a search for myself as a/r/tographer than anything else in the curation of this Portfolio. To begin this process, I selected a gallery in Blackheath, New South Wales to bring the digital and physical artist-researcher-teacher identities, spaces and sites together. This was to play a role in the physical site of artist self exploration and to play an integral role in my research and teacher selves, while writing the storied curriculum as a/r/tographer for this digital A/R/T Portfolio. The process of physically curating an installation of creative practice as research, was an opening of the digital portfolio, a physical space selected to take the narrative turn away from the creative and into the digital, to explore the connection between the physical site and digital site for curatorial practice as artist. This exhibition at Virgin Walls in Blackheath was a self portrait, a portrait as an a/r/tographer to present a/r/t research of my life over the last few years, lived within this inquiry. An exhibition of the artist-researcher, designed and curated as an educative, pedagogical and relational space to connect the participants as audience through a/r/tography.

The exhibition at Virgin Walls brought contiguity into clarity in the living inquiry. Here, sitting in the gallery I untangled the three identities of a/r/t to demonstrate how I used sight through the lens of artist-researcher-teacher. However, as a/r/tographer, when the identities are folded together, that creative possibilities are found in the inbetween. “The research conditions of a/r/tography reside in several notions of relationality; relational inquiry, relational aesthetics, and relational learning” (Irwin & Springgay, 2008, p. xxvii). The curated site in Blackheath was to explore another of the outcomes of this study - what does an artist think the portfolio reflects about practice and/or process? I needed to see, feel and respond to the differences in curatorial devices, actions and practice between sights as a/r/tographer as participant, just as Ahmad, Zahrah, Pam, Flavia, Belinda, Laurie, Pamela, Glenn and Sam had. I needed to play a role in connecting the physical and digital sites, to weave the two together and then untangle them to find the overlaps as the tenth co-particpating artist in the study. I found not only the commonalities in action and reflection, I also discovered the creative possibilities of digital spaces in comparison to the physical exhibition site. Both spaces, hold opportunities for creative affect, offer self reflective moments to see the interconnected themes and recurring ideas in practice over time through selection and curation. The both rely on similar skill sets and literacies. An artist portfolio in the digital space requires skills and competencies that can be designed into secondary art education curriculum for:

- Creativity

- Critical thinking and Problem Solving

- Design thinking and possibility thinking

- Visuacy

- Reflective practice

|

In the physical exhibition site, I also had to consider space, placemaking, safety, text and contact with the audience, all components of the digital. What was different, what is needed to be taught in the digital? Relationality through digital rhizomatic learning experiences, to create ongoing openings in the gaps and ruptures in the site for visitors. In the physical gallery, the audience’s sight is determined by the site. The cultural and social impacts of site all impact on the way you read the rooms. The conversation with the artist or invigilator as you enter, the sounds and amount of people in the room with you all effect your sensory experience, the temperature inside and outside, the size of the works and the amount of time you have to reflect before seeing another work, all impact your viewing and reading. The height of the plinths and affect of space and placemaking on the physical senses are all curatorial decisions that impact on the narrative that either invite you in, or sit in tangent with you as audience. The context, always affects and effects your experiences.

|

Curating context

Some a/r/tographers define the rhizomatic relations of a/r/tography through the lens of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (1987) who use the loaded word/thought/ideology/metaphor to describe theory and research that allows for multiple, non-hierarchical entry and exit points. For art educators the concept of rhizomatic learning is not a metaphor but a model for art encounters (O’Sullivan, 2006) in our classrooms: an a/r/tographic pedagogy that I seek to open for creativity. As Tardif and Sternberg (1988) as cited in Wielgosz and Imms (2007) found in their cognitive characteristics of creative people, the ability to be “alert to novelty and gaps in knowledge” and to “use existing knowledge as base for new ideas” is an important characteristic of rhizomatic and a/r/tographic pedagogy. The use of the term rhizomatic journey is often used by a/r/tographers (Irwin, 2013) to metaphorically visualise and conceptualise the patterns of and growth that their making, searching and writing takes. Similar to many of the pedagogies that so define what it is that art teachers embody, this term has been claimed by the wider field of online education (Cormier, 2008; 2013; 2014a; 2014b; 2014c; 2016; Mackness & Bell, 2015).

In Blackheath, the rhizomatic connections between the physical and digital sites were found in living within the inquiry in the in-between. The contiguity of spaces that portfolios enable as exhibitions was a profound turn. Each day, I wrote a quick reflexive summary of my reflections in Medium, an online magazine site. I posted photographs in Instagram, Facebook, and twitter and talked with locals and passersby as they entered the physical exhibition site. The rhizomatic space I encountered in this situation, has played a significant role in the design of these renderings, whereby a physical understanding of curation on site through installation and placemaking understanding, before designing and curating a digital space is necessary. Working across spaces in this practice, resulted in audiences in the physical and digital exhibition spaces and enabled participants locally, nationally and internationally at once. This opening of the physical site to digital space, created a connectedness between the physical and digital traversed space, made the invisible visible, and created opportunities for new interpretation and new meanings to be created in each of the sites. This rhizomatic and relational living inquiry interpretation, generated the conditions for reflection on the narrative of my practice to create new pedagogical opportunities.

The first artist monograph I owned was about American painter, Georgia O’Keefe. I have since lost this little book of flowers, clouds, bones and sky but my love affair with the monograph began in this little curated collection. My mum had gifted me this sometime in high school and I remember curating it in a self portrait bricolage I made at art school. I now own many of these collective monographic books. They explore bodies of work from some of my favourites and sit on carefully curated shelves with art works and kitsch collections in my house. I have always loved the narratives that they create, stories generated by the authors or curators’ essay about what the artist does. These little curated collections take you on a journey into an artist’s practice and explore stories through materiality. I am one of those art gallery visitors who is drawn to the capitalist art store to peruse the monographs and exhibition catalogues. I love these artefacts from exhibitions and they represent what I think religious people have in their love of bibles or crosses. They represent my faith and spiritual connections to art and artistry and house the stories of my artist loves. I have used my monographs as artist, researcher and as teacher and they have lovely bits of marginalia and marks of my own and students marks of artmaking throughout them.

The artist monograph is a curated collection that often represents a chronological, genré or thematically composed narrative of artwork and text. Artist monographs are curated to lead an audience through a narrative of an artist’s life and work. The Lives, by Georgio Vasari is one of the oldest versions I have in my collection of artist books. As Christopher Witcombe tells us, “The roots of the discipline we practice today emerged during the Renaissance, initially in the context of collecting art, and subsequently in the lecture halls of the art academy. A new technology, the printing press, contributed significantly to this development in two areas, that of the book and that of the print. Giorgio Vasari…was able to take advantage of the printing press to produce multiple copies of his book of artists’ biographies. This book provided both a framework and a methodology for the study of art history” (ND., NPN). Vasari offered his audience a biography of the lives of the Great Masters in his La Vite, or The Lives. He constructed a history of the Italian Renaissance, through his narrative account of the artists, generating a text for which both artist, researcher and patron could refer. He shared the stories for his colleagues and peers and to maintain these lives and with them what he thought the standards of male genius.

Vasari was a successful artist and architect when ‘The Lives’ was first published in 1550, dedicated to collector and patron, Cosimo de Medici. The Lives are shared by Vasari in three distinct sections: the preface which includes Cimabue to Giotto; Uccello to Mantegna and da Vinci to Titian. Vasari bases the stories in this collection of monographs around the birth, adolescence/youth and maturity of the Renaissance and constructs a conceptual framework or model that later used by his contemporaries, including Johann Winckelmann. This book is one of my favourite art texts in my collection for its use of personal narrative to describe the life, practice and work of these artists through the voice of artist, theorist and critic as dialogic. He shares with us his letters and personal accounts as a/r/tographer.

The Lives is a subjective and personal account of the ‘A’ rtist with a large section, the longest, dedicated to Vasari’s friend Michelangelo Buonarroti. Vasari narrates the life of Michelangelo through a personal narrative where he highlights the gifted nature of the genius with references to both God and instinct. “When I first undertook these lives I did not intend to compile a list of artists with say, an inventory of their works; and I was far from thinking it a worthwhile objective for my work to give details of their numbers and names and places of birth and describe in what city or exact spot their pictures or sculptures or buildings might be found. I could have done this simply by providing a straight-forward list, without offering any opinions of my own” (Vasari, 1965, p.83).

What this and other curated collections have that is so powerful, is the ability to see, read and learn about a body of work over time. The artist monograph is a visual metaphor for the rhizome of creativity and creative practice. It enables a visual of the rhizome branching out and developing new roots and shoots just as ideas and concepts grow in new spaces. If cut and moved, the rhizome can start and begin to shoot again. This reflection of creativity and creative practice across a career is a difficult concept to develop understanding of as a young artist in secondary school.

What can we learn from Vasari and other artist monographs to teach artist-students as they learn to curate their own art encounters with art as artist? What can artist students notice about practice through the exploration of artist monographs to support their development as artist? What can artist students learn about themselves as artists if they design and curate a portfolio as a monograph of the self as artist?

Vasari was a successful artist and architect when ‘The Lives’ was first published in 1550, dedicated to collector and patron, Cosimo de Medici. The Lives are shared by Vasari in three distinct sections: the preface which includes Cimabue to Giotto; Uccello to Mantegna and da Vinci to Titian. Vasari bases the stories in this collection of monographs around the birth, adolescence/youth and maturity of the Renaissance and constructs a conceptual framework or model that later used by his contemporaries, including Johann Winckelmann. This book is one of my favourite art texts in my collection for its use of personal narrative to describe the life, practice and work of these artists through the voice of artist, theorist and critic as dialogic. He shares with us his letters and personal accounts as a/r/tographer.

The Lives is a subjective and personal account of the ‘A’ rtist with a large section, the longest, dedicated to Vasari’s friend Michelangelo Buonarroti. Vasari narrates the life of Michelangelo through a personal narrative where he highlights the gifted nature of the genius with references to both God and instinct. “When I first undertook these lives I did not intend to compile a list of artists with say, an inventory of their works; and I was far from thinking it a worthwhile objective for my work to give details of their numbers and names and places of birth and describe in what city or exact spot their pictures or sculptures or buildings might be found. I could have done this simply by providing a straight-forward list, without offering any opinions of my own” (Vasari, 1965, p.83).

What this and other curated collections have that is so powerful, is the ability to see, read and learn about a body of work over time. The artist monograph is a visual metaphor for the rhizome of creativity and creative practice. It enables a visual of the rhizome branching out and developing new roots and shoots just as ideas and concepts grow in new spaces. If cut and moved, the rhizome can start and begin to shoot again. This reflection of creativity and creative practice across a career is a difficult concept to develop understanding of as a young artist in secondary school.

What can we learn from Vasari and other artist monographs to teach artist-students as they learn to curate their own art encounters with art as artist? What can artist students notice about practice through the exploration of artist monographs to support their development as artist? What can artist students learn about themselves as artists if they design and curate a portfolio as a monograph of the self as artist?

|

Laurie Gatlin

|

Samuel Massey

|

I’m sitting in the underground sculpture wing, where we work in clay in the damp studio spaces just off Oxford St. The floor is gritty and the tables always dusty. It was my first sculpture crit. I had never experienced this before. In high school I had been an avid user of my art diary, meticulously scrapbooking, annotating and justifying my ideas and concepts before handing in works for marking. For this first uni crit, I had carefully selected works to demonstrate my skills developed across this my first semester of art school. I had my art diaries, sketches, clay experiments and bisque fired Marquettes. I sat at my desk waiting for the group to get to me. I could see the questions posed to my peers were often difficult to respond to. The team made it to my area. Today, most of this memory has faded. What is ever present is the feeling of failure I had as a result of the session. My work was not what they expected to see. I had not done enough; I was not able to speak to my progression with enough experience. I had process oriented works, I had not taken the next step into resolved and final pieces of complete practice. I was stuck in the realm of creative possibilities, exploring my ideas and generating possible solutions to ideation, but not resolving my creative practice to resolve an idea, rather always testing its possibilities.

This sense-making reflection and account was both transformative at the time and today as I design portfolio assessment tasks. This insider understanding, of feeling underprepared for critique by the curation of my process, underprepared as a reflective practitioner, under prepared as an artist. These reflections continue to inform my practice as I teach students how to develop ideas, iterate, reflect, make, reflect and make, recording and documenting in a portfolio.

I still call art crits, crying crits, to this day.

Informed by secondary art curriculum and pedagogy to support students to gain skills in self identity through reflection on sustained creative practice to design and curate portfolios that demonstrate the common threads to the maker through deep learning. An A/r/tist in Wonderland is designed as the process, product and pedagogies of a/r/tographic praxis to provide a curriculum that opens a space to curate the self, an ‘eventful space’ (Fendler, 2013) for reflection that mirrors the body of work developed and invites creativity through identity formation for secondary art learners. Our curriculum authorities tell us that “a body of work is inclusive of both making and appraising. It shows a student’s progress through the inquiry learning model (researching, developing, resolving, reflecting), as he/she integrates the components of the course (concept, focus, context, media area(s) and visual language and expression). It enables students to use and develop a deep understanding and knowledge of artists, artwork, styles, process, media, through investigation of the purpose, practices and approaches of visual arts and artists to support their making and appraising, one enhancing and extending on information for the other.

In creating a body of work, students develop their ideas over time, exploring and experimenting with concept, focus, contexts and media area/s. The body of work comes to represent a coherent journey which may attempt divergent paths but eventually moves towards communicating visual meaning in the resolution of art work/s and in the consideration of the production and display of artworks to make informed judgments when ascribing aesthetic value, challenging ideas, investigating meanings, purposes, practices and approaches” (Queensland Studies Authority, 2007, p.2). The New South Wales curriculum informs us that, “understanding the notion of a ‘body of work’ requires an understanding of artists’ practice” (BOSTES, ND., p.70). Here in Victoria, “they focus on the development of a body of work that demonstrates creativity and imagination, the evolution of ideas and the realisation of appropriate concepts, knowledge and skills. At the [end of this unit], students present a body of work and at least one finished artwork accompanied by documentation of thinking and working practices” (VCAA, 2014. p.25). Body of work embodies sustained practice, connected and intertwined learning, making and doing. It is both an understanding and an experience of praxis. It is the consequence of a lived inquiry, difficult for young people to comprehend as the result of school art studies and one that I found difficult as a first year art student in university with explicit teaching, modeling and scaffolding. Through this study, this ethnography of artists and artist portfolios, I design this Portfolio to support and scaffold experiential learning through sustained deep learning and support my artist-students to generate work that reflects their commensurate developing identities through reflection on refection as curation.

In creating a body of work, students develop their ideas over time, exploring and experimenting with concept, focus, contexts and media area/s. The body of work comes to represent a coherent journey which may attempt divergent paths but eventually moves towards communicating visual meaning in the resolution of art work/s and in the consideration of the production and display of artworks to make informed judgments when ascribing aesthetic value, challenging ideas, investigating meanings, purposes, practices and approaches” (Queensland Studies Authority, 2007, p.2). The New South Wales curriculum informs us that, “understanding the notion of a ‘body of work’ requires an understanding of artists’ practice” (BOSTES, ND., p.70). Here in Victoria, “they focus on the development of a body of work that demonstrates creativity and imagination, the evolution of ideas and the realisation of appropriate concepts, knowledge and skills. At the [end of this unit], students present a body of work and at least one finished artwork accompanied by documentation of thinking and working practices” (VCAA, 2014. p.25). Body of work embodies sustained practice, connected and intertwined learning, making and doing. It is both an understanding and an experience of praxis. It is the consequence of a lived inquiry, difficult for young people to comprehend as the result of school art studies and one that I found difficult as a first year art student in university with explicit teaching, modeling and scaffolding. Through this study, this ethnography of artists and artist portfolios, I design this Portfolio to support and scaffold experiential learning through sustained deep learning and support my artist-students to generate work that reflects their commensurate developing identities through reflection on refection as curation.